Differential operators#

There are a huge number of possible ways to perform differencing in computational fluid dynamics, and BOUT++ is intended to be able to implement a large number of them. This means that the way differentials are handled internally is quite involved; see the developer’s manual for full gory details. Much of the time this detail is not all that important, and certainly not while learning to use BOUT++. Default options are therefore set which work most of the time, so you can start using the code without getting bogged down in these details.

In order to handle many different differencing methods and operations, many layers are used, each of which handles just part of the problem. The main division is between differencing methods (such as 4th-order central differencing), and differential operators (such as \(\nabla_{||}\)).

Differencing methods#

Methods are typically implemented on 5-point stencils (although exceptions are possible) and are divided into three categories:

Central-differencing methods, for diffusion operators \(\frac{df}{dx}\), \(\frac{d^2f}{dx^2}\). Each method has a short code, and currently include

C2: 2\(^{nd}\) order \(f_{-1} - 2f_0 + f_1\)C4: 4\(^{th}\) order \((-f_{-2} + 16f_{-1} - 30f_0 + 16f_1 - f_2)/12\)S2: 2\(^{nd}\) order smoothing derivativeW2: 2\(^{nd}\) order CWENOW3: 3\(^{rd}\) order CWENO

Upwinding methods for advection operators \(v_x\frac{df}{dx}\)

U1: 1\(^{st}\) order upwindingU2: 2\(^{nd}\) order upwindingU3: 3\(^{rd}\) order upwindingU4: 4\(^{th}\) order upwindingC2: 2\(^{nd}\) order centralC4: 4\(^{th}\) order centralW3: 3\(^{rd}\) order Weighted Essentially Non-Oscillatory (WENO)

Flux conserving and limiting methods for terms of the form \(\frac{d}{dx}(v_x f)\)

U1: 1\(^{st}\) order upwindingC2: 2\(^{nd}\) order centralC4: 4\(^{th}\) order central

Special methods :

FFT: Classed as a central method, Fourier Transform method in Z(axisymmetric) direction only. Currently available for

firstandsecondorder central difference

SPLIT: A flux method that splits into upwind and central terms\(\frac{d}{dx}(v_x f) = v_x\frac{df}{dx} + f\frac{dv_x}{dx}\)

WENO methods avoid overshoots (Gibbs phenomena) at sharp gradients such as shocks, but the simple 1st-order method has very large artificial diffusion. WENO schemes are a development of the ENO reconstruction schemes which combine good handling of sharp-gradient regions with high accuracy in smooth regions.

The stencil based methods are based by a kernel that combines the data

in a stencil to produce a single BoutReal (note upwind/flux methods

take extra information about the flow, either a BoutReal or

another stencil). It is not anticipated that the user would wish

to apply one of these kernels directly so documentation is not

provided here for how to do so. If this is of interest please look at

include/bout/index_derivs.hxx. Internally, these kernel routines

are combined within a functor struct that uses a BOUT_FOR loop

over the domain to provide a routine that will apply the kernel to

every point, calculating the derivative everywhere. These routines are

registered in the appropriate DerivativeStore and identified by

the direction of differential, the staggering, the type

(central/upwind/flux) and a key such as “C2”. The typical user does

not need to interact with this store, instead one can add the

following to the top of your physics module:

#include <derivs.hxx>

to provide access to the following routines. These take care of selecting the appropriate method from the store and ensuring the input/output field locations are compatible.

Function |

Formula |

|---|---|

DDX(f) |

\(\partial f / \partial x\) |

DDY(f) |

\(\partial f / \partial y\) |

DDZ(f) |

\(\partial f / \partial z\) |

D2DX2(f) |

\(\partial^2 f / \partial x^2\) |

D2DY2(f) |

\(\partial^2 f / \partial y^2\) |

D2DZ2(f) |

\(\partial^2 f / \partial z^2\) |

D4DX4(f) |

\(\partial^4 f / \partial x^4\) |

D4DY4(f) |

\(\partial^4 f / \partial y^4\) |

D4DZ4(f) |

\(\partial^4 f / \partial z^4\) |

D2DXDZ(f) |

\(\partial^2 f / \partial x\partial z\) |

D2DYDZ(f) |

\(\partial^2 f / \partial y\partial z\) |

VDDX(f, g) |

\(f \partial g / \partial x\) |

VDDY(f, g) |

\(f \partial g / \partial y\) |

VDDZ(f, g) |

\(f \partial g / \partial z\) |

FDDX(f, g) |

\(\partial/\partial x( f * g )\) |

FDDY(f, g) |

\(\partial/\partial x( f * g )\) |

FDDZ(f, g) |

\(\partial/\partial x( f * g )\) |

By default the method used will be the one specified in the options

input file (see Differencing methods), but most of these

methods can take an optional std::string argument (or a

DIFF_METHOD argument - to be deprecated), specifying exactly which

method to use.

User registered methods#

Note

The following may be considered advanced usage.

It is possible for the user to define their own

differencing routines, either by supplying a stencil using kernel or

writing their own functor that calculates the differential

everywhere. It is then possible to register these methods with the

derivative store (for any direction, staggering etc.). For examples

please look at include/bout/index_derivs.hxx to see how these

approaches work.

Here is a verbose example showing how the C2 method is

implemented.

DEFINE_STANDARD_DERIV(DDX_C2, "C2", 1, DERIV::Stanard) {

return 0.5*(f.p - f.m);

};

Here DEFINE_STANARD_DERIV is a macro that acts on the kernel

return 0.5*(f.p - f.m); and produces the functor that will apply

the differencing method over an entire field. The macro takes several

arguments;

the first (

DDX_C2) is the name of the generated functor – this needs to be unique and allows advanced users to refer to a specific derivative functor without having to go through the derivative store if desired.the second (

"C2") is the string key that is used to refer to this specific method when registering/retrieving the method from the derivative store.the third (

1) is the number of guard cells required to be able to use this method (i.e. here the stencil will consist of three values – the field at the current point and one point either side). This can be 1 or 2.the fourth (

DERIV::Standard) identifies the type of method - here a central method.

Alongside DEFINE_STANDARD_DERIV there’s also DEFINE_UPWIND_DERIV,

DEFINE_FLUX_DERIV and the staggered versions

DEFINE_STANDARD_DERIV_STAGGERED, DEFINE_UPWIND_DERIV_STAGGERED and

DEFINE_FLUX_DERIV_STAGGERED.

To register this method with the derivative store in X and Z with

no staggering for both field types we can then use the following code:

produceCombinations<Set<WRAP_ENUM(DIRECTION, X), WRAP_ENUM(DIRECTION, Z)>,

Set<WRAP_ENUM(STAGGER, None)>,

Set<TypeContainer<Field2D, Field3D>>,

Set<DDX_C2>>

someUniqueNameForDerivativeRegistration(registerMethod{});

For the common case where the user wishes to register the method in

X, Y and Z and for both field types we provide the helper

macros, REGISTER_DERIVATIVE and REGISTER_STAGGERED_DERIVATIVE

which could be used as REGISTER_DERIVATIVE(DDX_C2).

To simplify matters further we provide REGISTER_STANDARD_DERIVATIVE,

REGISTER_UPWIND_DERIVATIVE, REGISTER_FLUX_DERIVATIVE,

REGISTER_STANDARD_STAGGERED_DERIVATIVE,

REGISTER_UPWIND_STAGGERED_DERIVATIVE and

REGISTER_FLUX_STAGGERED_DERIVATIVE macros that can define and

register a stencil using kernel in a single step. For example:

REGISTER_STANDARD_DERIVATIVE(DDX_C2, "C2", 1, DERIV::Standard) { return 0.5*(f.p-f.m);};

Will define the DDX_C2 functor and register it with the derivative

store using key "C2" for all three directions and both fields with

no staggering.

Mixed second-derivative operators#

Coordinate derivatives commute, as long as the coordinates are globally well-defined, i.e.

When using paralleltransform = shifted or paralleltransform = fci (see

Parallel Transforms) we do not have globally well-defined coordinates. In those

cases the coordinate systems are field-aligned, but the grid points are at constant

toroidal angle. The field-aligned coordinates are defined locally, on planes of constant

\(y\). There are different coordinate systems for each plane. However, within each

local coordinate system the derivatives do commute. \(y\)-derivatives are taken in the

local field-aligned coordinate system, so mixed derivatives are calculated as

D2DXDY(f) = DDX(DDY(f))

D2DYDZ(f) = DDZ(DDY(f))

This order is simpler – the alternative is possible. Using second-order central difference operators for the y-derivatives we could calculate (not worring about communications or boundary conditions here)

Field3D D2DXDY(Field3D f) {

auto result{emptyFrom(f)};

auto& coords = *f.getCoordinates()

auto dfdx_yup = DDX(f.yup());

auto dfdx_ydown = DDX(f.ydown());

BOUT_FOR(i, f.getRegion()) {

result[i] = (dfdx_yup[i.yp()] - dfdx_ydown[i.ym()]) / (2. * coords.dy[i])

}

return result;

}

This would give equivalent results to the previous form [1] as yup and ydown give

the values of f one grid point along the magnetic field in the local field-aligned

coordinate system.

The \(x\mathrm{-}z\) derivative is unaffected as it is taken entirely on a plane of constant \(y\) anyway. It is evaluated as

D2DXDZ(f) = DDZ(DDX(f))

As the z-direction is periodic and the z-grid is not split across processors,

DDZ does not require any guard cells. By taking DDZ second, we do not have to

communicate or set boundary conditions on the result of DDX or DDY before taking

DDZ.

The derivatives in D2DXDY(f) are applied in two steps. First dfdy = DDY(f) is

calculated; dfdy is communicated and has a boundary condition applied so that all the

x-guard cells are filled. The boundary condition is free_o3 by default (3rd order

extrapolation into the boundary cells), but can be specified with the fifth argument to

D2DXDY (see Boundary conditions for possible options). Second DDX(dfdy) is

calculated, and returned from the function.

Non-uniform meshes#

examples/test-nonuniform seems to not work? Setting

non_uniform = true in the BOUT.inp options file enables corrections

to second derivatives in \(X\) and \(Y\). This correction is

given by writing derivatives as:

where \(i\) is the cell index number. The second derivative is therefore given by

The correction factor \(\partial/\partial i(1/\Delta x)\) can

be calculated automatically, but you can also specify d2x in the

grid file which is

The correction factor is then calculated from d2x using

Note: There is a separate switch in the Laplacian inversion code, which enables or disables non-uniform mesh corrections.

General operators#

These are differential operators which are for a general coordinate system.

where we have defined

not to be confused with the Christoffel symbol of the second kind (see the coordinates manual for more details).

Clebsch operators#

Another set of operators assume that the equilibrium magnetic field is written in Clebsch form as

where

is the background equilibrium magnetic field.

Function |

Formula |

|

\(\partial^0_{||} = \mathbf{b}_0\cdot\nabla = \frac{1}{\sqrt{g_{yy}}}{{\frac{\partial }{\partial y}}}\) |

|

\(\nabla^0_{||}f = B_0\partial^0_{||}(\frac{f}{B_0})\) |

|

\(\partial^2_{||}\phi = \partial^0_{||}(\partial^0_{||}\phi) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{g_{yy}}}{{\frac{\partial}{\partial y}}}(\frac{1}{\sqrt{g_{yy}}}){{\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y}}} + \frac{1}{g_{yy}}\frac{\partial^2\phi}{\partial y^2}\) |

|

\(\nabla_{||}^2\phi = \nabla\cdot\mathbf{b}_0\mathbf{b}_0\cdot\nabla\phi = \frac{1}{J}{{\frac{\partial}{\partial y}}}(\frac{J}{g_{yy}}{{\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y}}})\) |

|

\(\nabla_\perp^2 = \nabla^2 - \nabla_{||}^2\) |

|

Perpendicular Laplacian, neglecting all \(y\)

derivatives. The |

|

Poisson brackets. The Arakawa option, neglects the parallel \(y\) derivatives if \(g_{xy}\) and \(g_{yz}\) are non-zero |

We have that

In a Clebsch coordinate system \({{\boldsymbol{B}}} = \nabla z \times \nabla x = \frac{1}{J}{{\boldsymbol{e}}}_y\), \(g_{yy} = {{\boldsymbol{e}}}_y\cdot{{\boldsymbol{e}}}_y = J^2B^2\), and so the \(\nabla y\) term cancels out:

The bracket operators#

The bracket operator bracket(phi, f, method) aims to

differentiate equations on the form

Notice that when we use the Arakawa scheme, \(y\)-derivatives are

neglected if \(g_{xy}\) and \(g_{yz}\) are non-zero. An

example of usage of the brackets can be found in for example

examples/MMS/advection or examples/blob2d.

Finite volume, conservative finite difference methods#

These schemes aim to conserve the integral of the advected quantity over the domain. If \(f\) is being advected, then

is conserved, where the index \(i\) refers to cell index. This is done by calculating fluxes between cells: Whatever leaves one cell is added to another. There are several caveats to this:

Boundary fluxes can still lead to changes in the total, unless no-flow boundary conditions are used

When using an implicit time integration scheme, such as the default PVODE / CVODE, the total is not guaranteed to be conserved, but may vary depending on the solver tolerances.

There will always be a small rounding error, even with double precision.

The methods can be used by including the header:

#include "bout/fv_ops.hxx"

Note The methods are defined in a namespace FV.

Some methods (those with templates) are defined in the header, but others are defined in src/mesh/fv_ops.cxx.

Parallel divergence Div_par#

This function calculates the divergence of a flow in \(y\) (parallel to the magnetic field) by a given velocity.

template<typename CellEdges = MC>

const Field3D Div_par(const Field3D &f_in, const Field3D &v_in,

const Field3D &a, bool fixflux=true);

where f_in is the quantity being advected (e.g. density), v_in

is the parallel advection velocity. The third input, a, is the maximum

wave speed, which multiplies the dissipation term in the method.

ddt(n) = -FV::Div_par( n, v, cs );

By default the MC slope limiter is used to calculate cell edges, but this can

be changed at compile time e.g:

ddt(n) = -FV::Div_par<FV::Fromm>( n, v, cs );

A list of available limiters is given in section Slope limiters below.

Example and convergence test#

The example code examples/finite-volume/fluid/ solves the Euler

equations for a 1D adiabatic fluid, using FV::Div_par() for

the advection terms.

where \(n\) is the density, \(p\) is the pressure, and

\(nv_{||}\) is the momentum in the direction parallel to the

magnetic field. The operator \(\nabla_{||}\) represents the

divergence of a parallel flow (Div_par), and \(\partial_{||}

= \mathbf{b}\cdot\nabla\) is the gradient in the parallel direction.

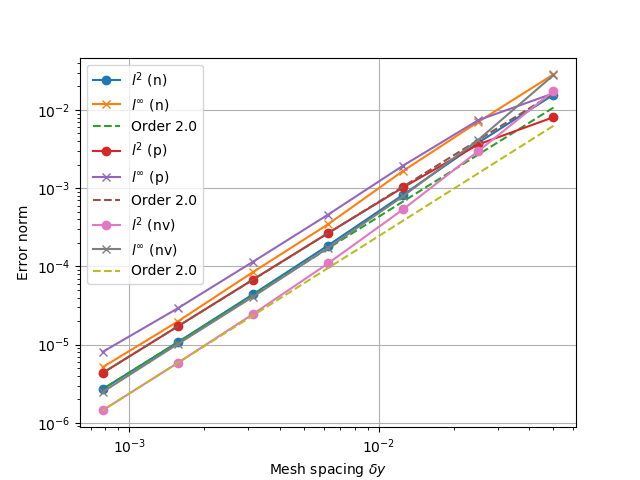

There is a convergence test using the Method of Manufactured Solutions (MMS) for this example.

See section Method of Manufactured Solutions for details of the testing method. Running the runtest

script should produce the graph

Fig. 16 Convergence test, showing \(l^2\) (RMS) and \(l^{\infty}\) (maximum) error for

the evolving fields n (density), p (pressure) and nv (momentum). All fields are

shown to converge at the expected second order accuracy.#

Parallel diffusion#

The parallel diffusion operator calculates \(\nabla_{||}\left[k\partial_||\left(f\right)\right]\)

const Field3D Div_par_K_Grad_par(const Field3D &k, const Field3D &f,

bool bndry_flux=true);

This is done by calculating the flux \(k\partial_{||}\left(f\right)\) on cell boundaries using central differencing.

Advection in 3D#

This operator calculates \(\nabla\cdot\left( n \mathbf{v} \right)\) where \(\mathbf{v}\) is a 3D vector. It is written in flux form by discretising the expression

Like the Div_par operator, a slope limiter is used to calculate the value of

the field \(n\) on cell boundaries. By default this is the MC method, but

this can be set as a template parameter.

template<typename CellEdges = MC>

const Field3D Div_f_v(const Field3D &n, const Vector3D &v, bool bndry_flux)

Slope limiters#

Here limiters are implemented as slope limiters: The value of a given

quantity is calculated at the faces of a cell based on the cell-centre

values. Several slope limiters are defined in fv_ops.hxx:

Upwind- First order upwinding, in which the left and right edges of the cell are the same as the centre (zero slope).Fromm- A second-order scheme which is a fixed weighted average of upwinding and central difference schemes.MinMod- This second order scheme switches between the upwind and downwind gradient, choosing the one with the smallest absolute value. If the gradients have different signs, as at a maximum or minimum, then the method reverts to first order upwinding (zero slope).MC(Monotonised Central) is a second order scheme which switches between central, upwind and downwind differencing in a similar way toMinMod. It has smaller dissipation thanMinModso is the default.

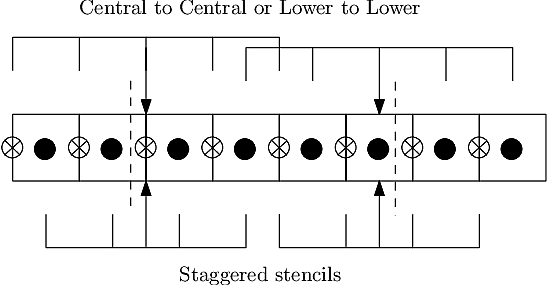

Staggered grids#

By default, all quantities in BOUT++ are defined at cell centre, and all derivative methods map cell-centred quantities to cell centres. Switching on staggered grid support in BOUT.inp:

StaggerGrids = true

allows quantities to be defined on cell boundaries. Functions such as

DDX now have to handle all possible combinations of input and output

locations, in addition to the possible derivative methods.

Several things are not currently implemented, which probably should be:

Only 3D fields currently have a cell location attribute. The location (cell centre etc) of 2D fields is ignored at the moment. The rationale for this is that 2D fields are assumed to be slowly-varying equilibrium quantities for which it won’t matter so much. Still, needs to be improved in future

Twist-shift and X shifting still treat all quantities as cell-centred.

No boundary condition functions yet account for cell location.

Currently, BOUT++ does not support values at cell corners; values can only be defined at cell centre, or at the lower X,Y, or Z boundaries. This is

Once staggered grids are enabled, two types of stencil are needed: those which map between the same cell location (e.g. cell-centred values to cell-centred values), and those which map to different locations (e.g. cell-centred to lower X).

Fig. 17 Stencils with cell-centred (solid) and lower shifted values (open). Processor boundaries marked by vertical dashed line#

Central differencing using 4-point stencil:

Input |

Output |

Actions |

|---|---|---|

Central stencil |

||

CENTRE |

XLOW |

Lower staggered stencil |

XLOW |

CENTRE |

Upper staggered stencil |

XLOW |

Any |

Staggered stencil to CENTRE, then interpolate |

CENTRE |

Any |

Central stencil, then interpolate |

Any |

Any |

Interpolate to centre, use central stencil, then interpolate |

Table: DDX actions depending on input and output locations. Uses first match.

Derivatives of the Fourier transform#

By using the definition of the Fourier transformed, we have

this gives

where we have used that \(f(x,y,\pm\infty)=0\) in order to have a well defined Fourier transform. This means that

In our case, we are dealing with periodic boundary conditions. Strictly speaking, the Fourier transform does not exist in such cases, but it is possible to define a Fourier transform in the limit which in the end lead to the Fourier series [2] By discretising the spatial domain, it is no longer possible to represent the infinite amount of Fourier modes, but only \(N+1\) number of modes, where \(N\) is the number of points (this includes the modes with negative frequencies, and the zeroth offset mode). For the discrete Fourier transform, we have

where \(k\) is the mode number, \(N\) is the number of points in \(z\). If we call the sampling points of \(z\) for \(z_Z\), where \(Z = 0, 1 \ldots N-1\), we have that \(z_Z = Z \text{d}z\). As our domain goes from \([0, 2\pi[\), we have that (since we have one less line segment than point) \(\text{d}z (N-1) = L_z = 2\pi - \text{d}z\), which gives \(\text{d}z = \frac{2\pi}{N}\). Inserting this is equation ((10)) yields

The discrete version of equation ((9)) thus gives

For more detail see Bracewell, R. N. - The Fourier Transform and Its Applications 3rd Edition chapter 10